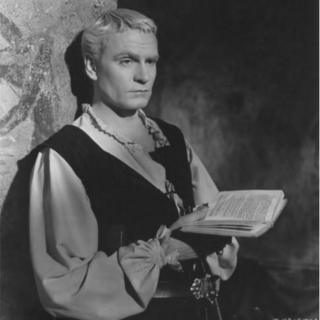

Image copyright

Alamy

Image caption

Sir Laurence Olivier in the 1948 film version of Hamlet

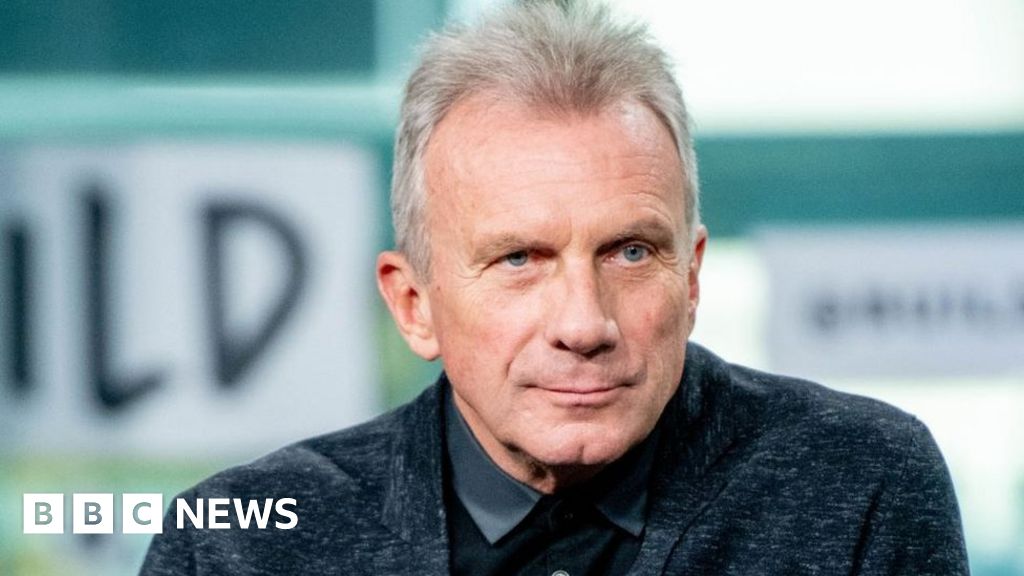

Image copyright

Alamy

Image caption

Sir Laurence Olivier in the 1948 film version of Hamlet

Spelling campaigners are taking "arms against a sea of troubles" in the latest skirmish in a 100-year-old battle to make written English easier to grasp.

A study suggests English-speaking children may take twice as long to learn to read and write as speakers of more regular languages because the spellings are so variable.

Now the English Spelling Society is using lines from Hamlet to demonstrate six spelling systems.

And the public, particularly parents who have been trying to teach their children during lockdown, are invited to vote for a winner, to be promoted as the society's official alternative to traditional English spelling.

Image copyright dorioconnell/Getty Images Image caption Hamlet's musings on "To be, or not to be" usually look something like thisEnglish is very irregular, partly because of the way it evolved - from Anglo-Saxon, via the Norman invasion, which introduced French words and spellings.

Also, early printers, who were paid by the letter, sometimes added extra letters to boost their earnings.

So words like "through" and "trough" are written almost the same, although they are pronounced completely differently.

It means children can struggle to master the basics, and many never do, resulting in 16.4% of adults in England, or 7.1 million people having very poor literacy skills, according to the National Literacy Trust.

Outrageous fortune

The English Spelling Society, which was founded in 1908 and counted playwright George Bernard Shaw as an early supporter, joined forces with the American Literacy Council two years ago and asked linguists to come up with viable alternative spelling schemes.

Of 35 proposals, six were shortlisted and the campaigners have used part of Hamlet's "To be, or not to be" soliloquy, some of the most famous lines in the English language, to demonstrate them.

Different spellings and typefaces mean early printed versions of the text looked very different from today's.

Image copyright MShieldsPhotos / Alamy Stock Photo Image caption The speech as printed in a 1623 version of the textThe new proposals range from the relatively conservative Traditional Spelling Revised to Read Script, which even changes the alphabet.

Silent letters are largely out, including double letters that do not change the sound of a word - and the creators aim for consistency in the way characters indicate sound.

Image copyright ESS Image caption Traditional Spelling Revised - one of the proposed spelling systems"We need to look at initiatives that will help people to master English spelling more quickly and without the teacher's red pen," says society chairman Jack Bovill.

"This is multi-generational and affects so many people.

"Poor literacy affects your chances in life. It can dictate what you earn, what careers are open to you and how likely a person is to spend time in prison."

Image copyright ESS Image caption Readscript - another of the suggested systems'Totally rude'

The subject has sparked a lively debate on the BBC's Family and Education Facebook page.

Marnie Weaver said when someone called her spelling "terrible" on social media, she made a joke out of it through sheer embarrassment.

Cathy Mizer called that sort of correction "totally rude".

"They do it for a distraction from the subject," she said.

Sandra Kamhieh-Milz said she would not normally correct spelling but admitted that in a recent argument with someone online, she "kept pointing out all her spelling errors to wind her up".

James Kirkhope said he, too, would not normally correct someone's spelling, but "if it's in a professional capacity by a professional person... then it looks bad".

For Sue Argent, who teaches English as an additional language, "our spelling system is a constant embarrassment".

She said: "Spelling reform would certainly speed up learning to read."

'ie see an aeroplaen'

The society says the aim is to find a formula that would allow for regional differences in pronunciation. It says there are no plans to alter the spelling of proper names - so the Cholmondeley family (pronounced Chumley) need not worry.

Of course, this is not the first attempt to reform English spelling.

Minor changes have included the removal of some extra letters - for example, the word "music" was once written "musick". In North America some words - for example, "color" - are written differently from their English equivalents - although, as the society points out, it's actually pronounced "culur" on both sides of the Atlantic.

During the middle of the last century, the Initial Teaching Alphabet (ITA), used more than 40 symbols to get children reading quickly.

The problem was, it just put off the day when they had to grapple with "real writing".

Image caption The Initial Teaching Alphabet may have been ahead of its time in terms of spelling - if not gender equalitySome struggled with having to learn to read twice or never quite got to grips with traditional English, and ITA eventually fell out of widespread use.

"It scarred me for life," says one woman, now a senior doctor in her 50s, who started to read using ITA and then transferred to another school that used traditional methods.

"I was really behind and couldn't read at all," she says.

Image copyright ESS Image caption The six options have some factors in commonThe campaigners suggest any new system be introduced alongside traditional spelling in the hope it eventually becomes the default option.

They believe that to a certain extent this is already happening as simpler, shorter SMS spellings are embraced by mobile-phone users who still use traditional spelling in other contexts, particularly at work.

Red ink

But Queen's English Society president Bernard Lamb says learning two systems will "result in confusion... especially for less able children".

"That sounds like cruelty to me," he says.

Another key question was whether people "could write a new system, as well as read it", Mr Lamb says.

"The answer for Read Script would surely be, 'No,'" he says.

"I suspect that those voting for different schemes for the Hamlet quotation will mainly choose Traditional Spelling Revised as that is closest to normal spelling and that few will go for Read Script, which looks awful and alien.

"It contains so many weird letters, including ones the wrong way round, and would be very difficult to master, difficult to write and require a revolution in machines to cope."

Dr Lamb blames poor spelling on lack of correction, adding his primary-school English book was "littered with red-ink corrections."

"The red ink never did us any harm," he says.

"We were used to it and expected it if the teacher wanted to help us improve."

'Achieve consensus'

The society is inviting comment on the schemes on its blog.

To vote you need to register for the English Spelling Congress, which will run entirely online in late 2020 and is free to join.

"The object is to open up the debate to all English speakers who are interested in spelling reform, not just academics or specialists," says committee member Stephen Linstead.

"We want to achieve consensus on a scheme that will improve access to literacy but also one that does not introduce unnecessary changes that would be unacceptable to the general public.

"Every vote will count equally, whoever the participant," he promises.

5 years ago

736

5 years ago

736