Image copyright

Sue Mitchell

Image copyright

Sue Mitchell

Many people would feel happier if they knew they had already had Covid-19, but the antibody tests designed to answer this question are not 100% reliable. Dr John Wright of Bradford Royal Infirmary was therefore pleased when a local choir, which had Covid-like symptoms as early as January, got the opportunity to take a T-cell test, the gold standard for prior Covid infection.

Four months into the pandemic and there is one burning question on the lips of every one of our front-line staff. Have they had Covid-19? Many doctors and nurses had symptoms in the early weeks when testing was shambolic, so have never had the diagnosis confirmed. The majority of staff have remained asymptomatic but we know that over half of cases display no symptoms.

The roll out of large-scale antibody testing is the opportunity we have all been waiting for. We don't know how long immunity lasts, so we know that there will be no "immunity passport", but intuitively it is better to have had the infection and have some protection than not to have had it and be back at the starting line, waiting nervously for the virus to strike. So unlike Ebola, HIV or recreational drug tests this is one where, deep down, we all want to test positive.

An unexpected delivery of home testing kits arrives in our Clinical Research Facility and my colleague Dinesh Saralaya and I decide to take the plunge and find out if we have had the lurgy. An anxious 10-minute wait and long, silent drum roll while we wait for the lines to appear on our pregnancy test-like strip: mine turns out positive, Dinesh's negative.

Image copyright John Wright Image caption Our test results - one positive for previous infection (left), the other negativeI am like a child at Christmas and have to hide my joy. Dinesh, in contrast, is glum but resigned. I try to cheer him up by telling him it shows how good he has been at wearing PPE.

A few days later and we both have the hospital laboratory antibody test. This time mine comes back negative and I take the mantle of glumness from Dinesh's shoulders. Well, at least I have been wearing my PPE properly.

Image caption My second test is negative - and Dinesh Saralaya is not especially sympatheticIt turns out that quite a few staff who had Covid symptoms or positive swabs have had negative antibody tests. I can hardly believe that anyone working in the hospital in the first few weeks of the epidemic managed to avoid such an infectious virus, particularly when the PPE was so inadequate.

Studies from across the world are finding that less than 10% of people have Sars-CoV2 antibodies, even in countries that have been badly hit by the virus. This is rather depressing, as it suggests that we are a long way from the infamous herd immunity that could protect us in the long term.

But a quick investigation into the accuracy of antibody tests uncovers doubts about their reliability. They have been evaluated on small numbers of hospitalised patients, from the more severe end of the spectrum and so may not detect antibodies in milder cases. Antibodies are also just one part of our immunity. They are produced from our B-cells (a type of white blood cell) in response to attacking antigens from viruses or bacteria. We also have T-cells (another type of white blood cell) that have a longer memory for past infections and help protect the body from subsequent infections.

Antibody immunity tests are quite easy to develop and part of everyday hospital investigations. T-cell immunity tests are trickier, but we do use them for diagnosing infections such as latent tuberculosis.

Front line diary

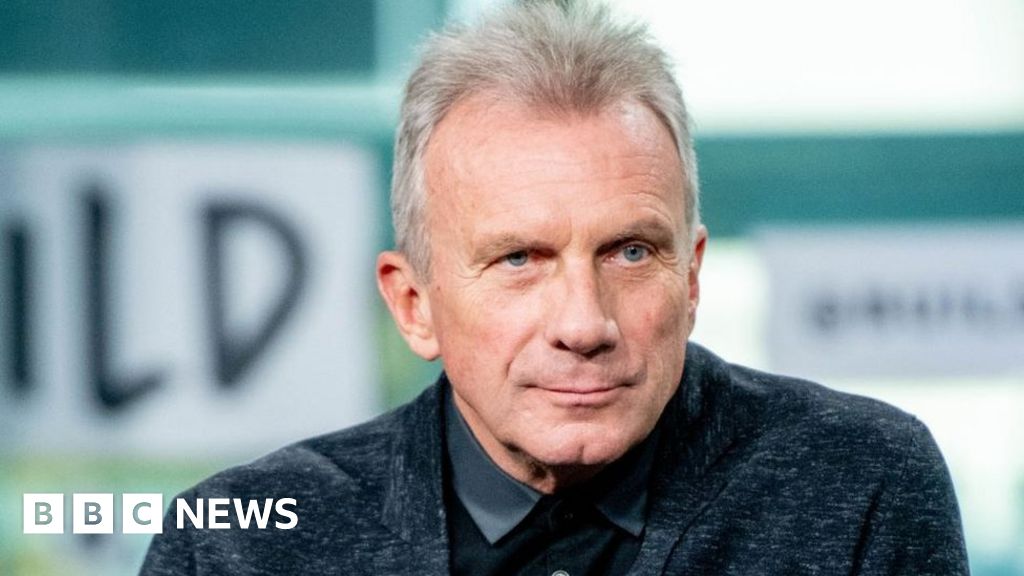

Image copyright Tom LawtonProf John Wright, a doctor and epidemiologist, is head of the Bradford Institute for Health Research, and a veteran of cholera, HIV and Ebola epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa. He is writing this diary for BBC News and recording from the hospital wards for BBC Radio.

Listen to the next episode of The NHS Front Line on BBC Sounds or the BBC World Service Or read the previous online diary entry: She's fit, young and has been ill with Covid for monthsA study from the Karolinska Institute in Sweden examined the blood of 200 blood donors and their family members and found that about 30% had evidence of T-cell immunity, despite the fact that many had had no symptoms, and had no measurable antibodies. Studies from other countries are also finding evidence of T-cell memory in people who have never been exposed to Covid-19, perhaps related to other "common cold" coronaviruses.

This is potentially good news and suggests that many more of us have been infected than antibody testing is finding, or have some cross-immunity to other similar viruses. The next big question is whether or not this T-cell immunity will provide protection against Covid-19 in the short or long term.

This brings me to the choir. Ever since I wrote about the local singers who had symptoms reminiscent of Covid-19 as long ago as January - before the first officially recognised case in the UK - people have not stopped questioning me about it. "So, did they have the virus or not?" they ask.

With the help of colleagues from the University of Oxford, who are running a national study on Covid-19 immunity, we were able recruit some of the choir members to test both antibody and T-cell immunity. At the end of the clinic session there was one testing kit left, so I eagerly volunteered: having had one positive and one negative antibody test I was itching to find out more about my T-cell immunity. (It's a shame there weren't two kits - Dinesh would have leapt at the possibility of getting a positive result after his two negative antibody tests.)

Prof Paul Klenerman of the Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, who offered to do the tests, points out that the immune system's memory of coronavirus fades over time, so may not get picked up without a sensitive test. It is, after all, six months since the first choir members became ill.

"We will look for cells that have gone to sleep - these can provide very good protection but they're harder to find," he says. "You have lots of T-cells at the beginning and can measure them in the blood, then they go back into the lymphoid tissue and the lymph nodes in the spleen and there are some in the blood, but you have to wake them up again. So we will do a proliferation assay, where we give them a few days to get going and give them something that mimics the virus, and see if they can respond to that."

After two weeks of intensive laboratory work, the results come back. The choir members and the landlady of the Bulls Head in Baildon - whom the singers appear to have infected with their virus - are all negative, for both antibodies and T-cell memory. This is fairly persuasive evidence that they did not in fact have Covid-19 and shows that there are other nasty viral illnesses out there, not to mention flu, that can sometimes make people ill enough to need hospital treatment.

Image copyright Sue Mitchell Image caption Pub landlady Juanita Kearns was taken to A&E in an ambulance - her T-cell test was also negativeI received a downcast email from Jane Hall, the singer pictured at the top of this story, who first brought the choir's illness to my attention.

"I don't know what we all had but it was very similar to Covid in so many ways and there were just so many people asking the question that once I found the possible link I felt it should be brought to the attention of a medical expert," she wrote. "I am disappointed with the results as it would have been good to know I had had it."

When I first wrote about the choir I mentioned that other people had also told me they'd experienced coronavirus-like symptoms before the virus's recorded arrival in this country - and I said I had generally reassured them that it was most likely a different viral infection. What made the choir's case stand out was their loss of taste and smell, and an intriguing link to Wuhan - the infections began after the return of one of the singer's partners from a business trip to the city in December. As I have said before, an epidemiologist always looks at person, place and time.

But in this case we now have a convincing negative result.

For those who had the symptoms without an obvious link to Wuhan, I would still say that it is highly likely that, like the choir, you had a different virus. As I also wrote in my first diary about the choir though, in all epidemics, when you start tracking back, you find that there were cases long before you became aware of them. The first confirmed case of transmission in this country came at the end of February. I still expect we'll discover that some people caught it in the UK before that.

As for me, while my results came back negative for antibodies, my CD8 T-cell memory was said to be consistent with prior exposure to Sars-CoV2.

This positive test is a ray of hope. It suggests that I have been infected, and it might provide longer-term protection, or reduce symptoms if I get infected again. However, as we write at the end of every scientific paper, more research is needed.

Follow @docjohnwright and radio producer @SueM1tchell on Twitter

5 years ago

604

5 years ago

604